In March, RuPaul’s Drag Race, a reality competition show in search of “America’s Next Drag Superstar,” featured a mini-game called “Female or She-male.” Contestants looked at pictures of bodies and tried to guess whether the person in the picture was a drag queen or a cisgender (not transgender) woman. This prompted a backlash from many transgender activists, who were upset by the nature of the segment and its use of the word “shemale,” which GLAAD explains is a term that “dehumanizes transgender people and should not be used.”

After an initially weak response to the outcry, Logo TV, the LGBT-focused network that airs Drag Race, announced it was pulling the episode and also cutting the “You’ve got She-mail!” segment that has been part of every episode of the show over its six seasons. Despite the resolution, the incident has continued to be a flashpoint about how the visibility of drag culture on Drag Race impacts public understanding of what it means to be transgender. Questions about the appropriate use of words like “shemale” and “tranny” speak to a larger conflict over media representation and the authenticity of identities.

RuPaul, the show’s host and executive producer, has been unrepentant, telling comedian Marc Maron recently, “I love the word ‘tranny,’” and that it’s only “fringe people” who are taking exception with such language. But among those “fringe people” expressing concern are former contestants from Drag Race, including Carmen Carrera and Monica Beverly Hillz, both of whom now identify as trans women. According to Hillz, she is still fighting for respect from society, because “people don’t understand the daily struggle it is to be a transgender woman.”

Hillz’s point is at the center of the conflict, because Drag Race is a show that is not about being transgender but that clearly has implications for transgender people — a particularly vulnerable population. People who identify as transgender report incredibly high rates of discrimination across their lives, including in employment, housing, health care, education, and police interactions. The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Program’s recent study found that 72 percent of all violent crimes against LGBTQ people in 2013 targeted transgender women, who also made up 67 percent of LGBTQ homicide victims. One of the most alarming statistics, that 41 percent of transgender people have attempted suicide — compared to just 1.6 percent of the general population — reflects the mental health consequences that result from this discrimination, harassment, and violence.

At the same time, the ongoing conversations about language sparked by Drag Race reflect what Time magazine recently called “the transgender tipping point.” With spokespeople like Laverne Cox (Orange Is The New Black) and Janet Mock speaking regularly to mainstream media outlets, visibility for transgender people — especially trans women of color — is on the rise. There have also been many victories for transgender equality, such as California’s new law and court rulings in Maine and in Colorado protecting transgender students. Maryland just became the 18th state to enact nondiscrimination protections based on gender identity, and exclusions for transgender health needs have been lifted for both Medicare and federal employees’ health insurance programs.

In many ways, the feud over Drag Race seems to stem from the visibility that the LGBT community has increasingly achieved, and an instinct to defend the authenticity of particular identities. For example, several drag performers responded aggressively against calls not to use words like “tranny,” suggesting it was word-policing and that reclaiming epithets is part of drag culture. Trans women have expressed their own concern that, if conflated with drag queens — i.e. “men in dresses” — the validity of their own identities will be questioned, further contributing to the oppression they experience.

In reality, as several Drag Race contestants outlined to ThinkProgress, this debate is circling some complicated conversations about identities that violate gender and traditional gender roles, but are not so neatly defined as “trans woman” or “cis man.”

“You can fully transform yourself. It’s as easy as deciding to transform yourself.”

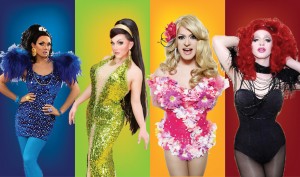

Drag, in its most commonly understood form, might be defined as gay men portraying sensationalized women for entertainment purposes, but those who do drag describe it as something more significant than that. Each queen has their own personal reasons for doing drag and expectations for what they hope it can accomplish beyond making an audience laugh.

Benjamin Putnam, better known as RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 6 contestant BenDeLaCreme, told ThinkProgress that for him, drag is about “dismantling that perception that we think we have about knowing what gender is.” Gender is a very “base thing,” Putnam explained, something we notice about a person even before their race, and drag creates an opportunity to question those expectations — ideally to improve the ways that we can be “kinder and treat each other better.”

Read more on this article at : ThinkProgress.org